The Challenges of Funding a CEM Strategy…

The Challenges of Funding a CEM Strategy…

A few weeks back, I was talking to a client about their latest strategies to enhance what is now known commonly as “the customer experience.” And like most companies that are working tirelessly on driving their customers toward higher levels of satisfaction, delight, and our latest aspiration, “engagement,” this company was going through all the common challenges of funding their new Customer Experience Management (CEM) strategy.

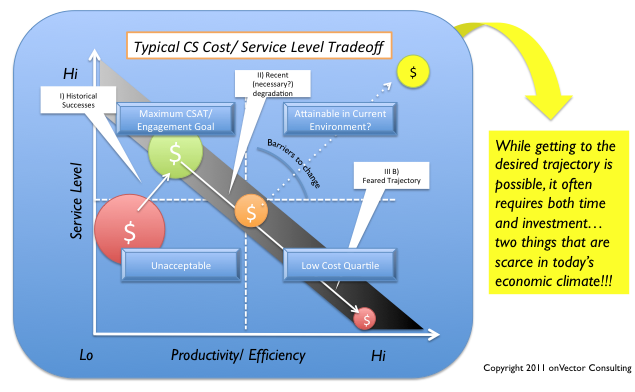

But also, like many others, funding their CEM strategy is meeting some pretty big resistance from their CFO and others who are trying to make corporate “ends meet,” especially in this economic climate. More and more, these two perspectives are clashing, not because the organization fails to value investment in Customer Service (CS), but more so because the impacts associated with that those investments are often less direct and less tangible, at least compared with the realm of immediate cost and productivity savings that produce faster (albeit not always sustainable) payback to the bottom line.

The Cost/ Service Trade-off: Myth or Reality?

For over two decades of working in the Customer Operations arena, I’ve heard clients invariably revert to the “perceived” trade-off between customer service levels and cost savings or efficiency efforts. That is, the notion that there is an inverse relationship between our ability to improve service levels and our ability to capture CS related productivity and cost savings. And for a long time, the data supported this notion. But as technologies improved, and companies began to increase investments in CS-related technology, tools and process changes, select companies started to prove that notion false by demonstrating the existence of both high service levels and low cost at the same time–companies clearly worthy of the term “myth busters”.

Yet despite all those great examples from the 90’s, we are now seeing many return to the proverbial “trade-off” as a reason for deferring further investments in their CS infrastructure. Make no mistake, there are clearly companies that are pushing the envelope of customer delight, and perhaps even engagement, but more often than not, investments in CEM, and even critical investments in basic infrastructure, are once again hitting the funding wall.

Some of this is clearly driven by the current economic climate. As a CEO from one of my energy clients said recently, “We haven’t given up on CS. But these investments are discretionary, and right now we are struggling to ‘keep the lights on'”. And, while on the surface, this may provoke emotions of heresy from those in highly competitive markets, it’s hard to argue with financial realities. At one time or another, most CS executives, regardless of industry, have encountered this same argument from their C-Suite executives.

Some of this is clearly driven by the current economic climate. As a CEO from one of my energy clients said recently, “We haven’t given up on CS. But these investments are discretionary, and right now we are struggling to ‘keep the lights on'”. And, while on the surface, this may provoke emotions of heresy from those in highly competitive markets, it’s hard to argue with financial realities. At one time or another, most CS executives, regardless of industry, have encountered this same argument from their C-Suite executives.

Unfortunately, for some, the lack of investment in that infrastructure has created a bit of a back-slide in performance, creating the question of whether we are back to the days of the proverbial trade-off.

Reversing The Course…

As with most things in life, the cup can be either half empty or half full based simply on the lens through which we are looking.

Sure, we all want to delight our customers and make them happy. But from a financial perspective, there is always an ROI at play, and it’s not always easy to establish a causal linkage between that “added delight factor” and the bottom line. Hence the conflict.

But this assumes we are trying to impress, delight, or otherwise “engage” the customer for the sole purpose of selling more of our product or service. And that is clearly part of it. But again, at the risk of offending our hardcore sales and product advocates (of which I am one), I would assert that there are many other reasons for having an engaged customer that go far beyond the next product sale or any direct influence on buying behavior at all.

Beyond the Obvious…

From my perspective, “Engagement” is about changing the overall predisposition of a customer from one of negative predisposition or neutrality, to one of positive engagement that is leveragable in some context. That context could be higher sales, repeat business, or Word of Mouth (WOM) referrals, but it could also serve a variety of other purposes.

One of those purposes is cost savings. What?

That’s right, cost savings.

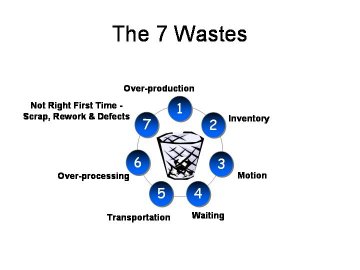

Over the past several years, we’ve completed a variety of assignments that were geared to identifying efficiencies where the mandate was “zero degradation to Customer Satisfaction”. Not an insignificant challenge. Especially when you consider that most companies have explored every way under the sun to drive more productivity out of their workforce, and have automated just about everything they can automate. And in some cases, these efforts have in fact degraded service level.

But many of those changes were inflicted on customers in a “push fashion”. Sure we’ve made tons of good changes in everything from local office closures, to call center automation improvements, to web interaction, but many of those changes were “pushed on the market” regardless of the level of satisfaction or disposition it happened to be in at the time. Yet we still wonder why the acceptance rates on what may appear to be wonderful customer options are at levels well below their potential. Experts claim that something as basic as “paperless billing” should be hitting 50-70% saturation in the next 3 years, but most of us are only at a fraction of those levels. But to me that is not surprising, given that we have not yet engaged the customer who we are asking to accept these changes. At least not in the spirit of how it is defined above.

Engagement for the Sake of Cost Reduction ?

Just for a second, put on your CFO hat and consider the following argument.

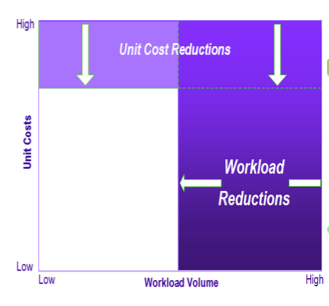

Cost is a product of both efficiency and transaction volume. We can decrease cost per transaction by 5,10, or even 20% in the form of cost-per-call, cost-per-bill, cost-per-payment, and the litany of other transaction types we offer. But the large majority of cost still remains.

Cost is a product of both efficiency and transaction volume. We can decrease cost per transaction by 5,10, or even 20% in the form of cost-per-call, cost-per-bill, cost-per-payment, and the litany of other transaction types we offer. But the large majority of cost still remains.

Now think about the other side of the equation. Transaction volume. Different story entirely. When we eliminate a transaction, be it a printed bill, a mailed payment, or a call to the call center, we eliminate 100% of the cost. Looking at it this way, there is no question where our focus should be. And looking at the potential that our recent advances in technology could have on enabling these reductions in transaction volume, it’s rather amazing that such a large part of our focus is still on operating and productivity gains.

On this basis, and given the potential that exists in the workload dimension alone, it is conceivable that savings of 30, 50%, or more are possible, and go well beyond what we would ever consider from mere productivity gains.

It all starts with Impacting Predisposition and Behavior…

Given the impact of workload on bottom line, why wouldn’t that become our primary focus?

Perhaps it should be. Or at least one of our primary goals. But haphazardly looking for where we can drive customers to self-service channels without a clear strategy will get us right back to square one. The “win win win” (CCO, CFO, and Customer) if you will, is only achievable if the levels of potential I describe above are fully realized, and accomplished in a manner that leaves the customer satisfied and engaged.

Engagement is about changing customers’ predisposition from negative or neutral to positive and engaged. Once that is accomplished, there exist numerous ways to leverage that engagement, including getting the customer to willingly shift the nature and frequency of their interactions with us, thus decreasing transaction volume. But that is only the tip of the iceberg, as the companies mastering this dynamic are finding out.

But it all starts with the lens we look through.

So next time you are faced with hitting that infamous “funding wall”, or get challenged on the basis of your new CEM strategy, think beyond the obvious.

-b

For more on driving Customer Excellence through combined efficiency and service level focus, see the folloowing posts on EPMEdge.com . Related articles include:

- Lagniappe, Purple Gold Fish, King Cakes and Customer Delight!

- The Mythology of (the customer) Apology

- When Did “Common Sense” Go Extinct from the workplace?

- To “Meet or Exceed” Customer Expectations? The answer may surprise you…

- A Recent Rant – Rare but necessary

- Putting the Customer back into Customer Service

- The Primary Fuel of Customer DISSATISFACTION

- CSAT-The Bigger Picture

- First Things First- Process BEFORE Technology

Author: Bob Champagne is Managing Partner of onVector Consulting Group, a privately held international management consulting organization specializing in the design and deployment of Performance Management tools, systems, and solutions. Bob has over 25 years of Performance Management experience and has consulted with hundreds of companies across numerous industries and geographies. Bob can be contacted at bob.champagne@onvectorconsulting.com

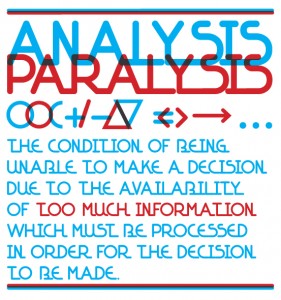

Analysis– When many companies hear the word “analysis”, they go straight to thinking about how they can better “work the data” they have. They begin by taking their scorecard down a few layers. The word “drill down” becomes synonymous with “analysis”. However, while they each are critical activities, they play very separate roles in the process. The act of “drilling down” (slicing data between plants, operating regions, time periods, etc.) will give you some good indication where problems exist. But it is not “real analysis” that will get you very far down the path of defining root causes and ultimately bettersolutions. And often, it’s why we get stuck at this level. Continuous spinning of the “cube” gets you no closer to the solution unless you get there by accident. And that is certainly the long way home. Good analysis starts with good questions. It takes you into the generation of a hypothesis which you may test, change and retest several times. It more often than not takes you into collecting data that may not (and perhaps should not) reside in your scorecard and dashboard. It requires sampling events and testing your hypotheses. And it often involves modeling of causal factors and drivers. But it all starts with good questions. When we refer to “spending more time in the problem”, this is what we’re talking about. Not merely spinning the scorecard around its multiple dimensions to see what solutions “emerge”.

Analysis– When many companies hear the word “analysis”, they go straight to thinking about how they can better “work the data” they have. They begin by taking their scorecard down a few layers. The word “drill down” becomes synonymous with “analysis”. However, while they each are critical activities, they play very separate roles in the process. The act of “drilling down” (slicing data between plants, operating regions, time periods, etc.) will give you some good indication where problems exist. But it is not “real analysis” that will get you very far down the path of defining root causes and ultimately bettersolutions. And often, it’s why we get stuck at this level. Continuous spinning of the “cube” gets you no closer to the solution unless you get there by accident. And that is certainly the long way home. Good analysis starts with good questions. It takes you into the generation of a hypothesis which you may test, change and retest several times. It more often than not takes you into collecting data that may not (and perhaps should not) reside in your scorecard and dashboard. It requires sampling events and testing your hypotheses. And it often involves modeling of causal factors and drivers. But it all starts with good questions. When we refer to “spending more time in the problem”, this is what we’re talking about. Not merely spinning the scorecard around its multiple dimensions to see what solutions “emerge”.

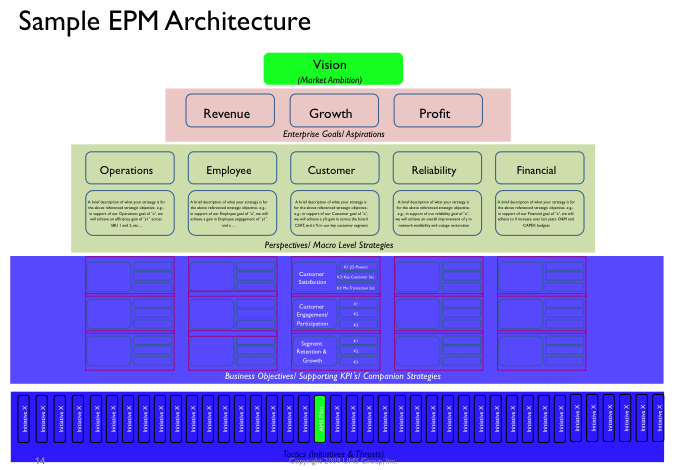

One of the questions I get asked often by my clients is “just how many KPI’s and metrics are enough for effective Performance Management to occur?”

One of the questions I get asked often by my clients is “just how many KPI’s and metrics are enough for effective Performance Management to occur?”